No societies have ever remained the same and the three towns of our Bay are not exceptions.

Change is always happening. Institutions and social organisations change; relationships and rules of behaviour change; culture and value systems change.

Sometimes change from above can be rapid. In 1539 the canons of Torre Abbey surrendered to King Henry VIII's commissioner. The Abbey had been established in 1196 but abruptly an entire medieval way of life ended in the greatest landgrab since the Norman Conquest.

Some impositions can be welcome, taking forward a positive response to real need. This was the case with the introduction of pensions in the early twentieth century and the welfare state after World War Two. For the first time the elderly could retain their dignity, all could be liberated from absolute poverty, much of the fear of unemployment faded, and the scourge of preventable sickness lessened.

So, what are the causes of change?

There are no fixed borders between environmental, social, economic, technological, and political change. They are often intertwined though we can recognise themes that appear throughout our history.

Who makes the Bay their home is our first cause of change. 1500 years ago, Devon was Dumnonia, homeland of the Dumnonii Brittonic Celts. Then incomers we know as the Anglo-Saxons moved in and by the ninth century we see a replacement of local British placenames by English ones; Paignton, Babbacombe, and Totnes being examples.

We are now seeing other migrations caused by globalisation and climate change. Torbay will not be insulated from the movements of millions of people, and our culture will inevitably evolve as a consequence.

New technologies have a significant impact. Torquay is a good illustration of how an insignificant scattering of rural and fishing hamlets was remade through the harnessing of the power of steam.

At the close of the eighteenth-century Torquay’s population was less than 800, most living around the harbour and in the settlement at Torre. During the following decades these settlements merged to become a popular health spa. Nevertheless, the town only grew slowly to around 6,000 by the 1840s.

It was the rise of capitalism and Empire which fundamentally altered the Bay’s economic system, creating new social classes, family structures, new ways of working, and altering relationships between individuals and communities.

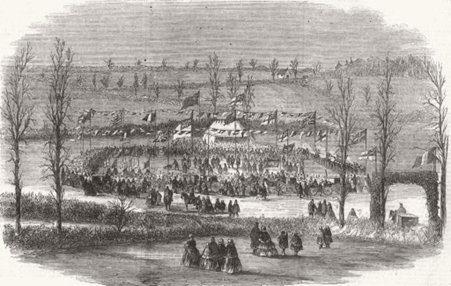

Bringing all of these changes to Torbay was the arrival of the railway in 1848. Within ten years the population had doubled as Torquay became a new type of Victorian town, the tourist resort. Overcrowding and poor sanitation, on the other hand, inevitably led to squalor and disease which demanded that our urban areas be planned and redeveloped for a new era.

The coming of the railways in 1848

The coming of the railways in 1848

Celebrating the extension of the Dartmouth and Torbay Railway in Avenue Road in 1858

By the close of the century the population stood at 33,000. Visitors were attracted by the Bay’s beauty, while others came to live, to work, or to retire. Thousands of individual choices were made, some by powerful families such as the Carys and the Palks, but many by those unremembered.

They all, nevertheless, contributed to making Torquay the leisure centre of the world’s largest empire. Yet, the decision to make Torquay and Paignton tourist towns have left a legacy; the Bay now has the third lowest incomes in the nation.

Individuals changing their minds and behaviours might seem insignificant. Yet, these personal decisions have long-term consequences as they serve as building blocks for fundamental shifts in how our wider society functions.

One of the most notable differences between today and a century past is in the nature and composition of the family. Long gone are the days of the clear division of roles and hierarchies of the Victorian and Edwardian household, with the father at the head and women expected to manage the home and raise any children.

Accelerated by war and the introduction of the welfare state, there were gradual changes to this traditional nuclear family throughout the early twentieth century. Then the sexual and cultural revolution of the 1960s saw a rapid transition to a more equal, though perhaps less cohesive, society.

Women in the nineteenth century bore an average of more than six children. In Torbay women now have an average of 1.4 children. Families are smaller and made up of a shifting mosaic of nuclear units, married and unmarried partners of any gender, and shared-custody arrangements. The numbers of children not living in a household with both natural parents has increased from 9% in 1960 to over 40% now.

Local folk have never been the passive recipients of economic and social forces, however. Social movements have always emerged to demand change. The long campaign for democracy, for instance, began with Torquay’s Chartists secretly meeting back in 1846 to campaign for the right to vote. However, it wasn’t until the Representation of the People Act in 1918 that all men gained the franchise.

This insistence on reform is often driven by charismatic leaders able to motivate a group of followers willing to break established rules. In 1866 Mary Caroline Cockrem of 10 Strand, Torquay was among 1,500 women from across the nation who signed a ground-breaking petition to extend the vote to women.

Taking up the struggle was Torquay’s Suffragette Organiser Elsie Howey (1884-1963), always “in the vanguard of militancy”, though it took until 1928 for the female voting age to be lowered to 21 - in line with men.

A more recent example of societal attitudes shifting is in the equal treatment of sexual orientation. Torquay now hosts a popular annual Pride event, celebrating the rights, dignity, equality, and increased visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. The decriminalisation of sexual activity between men only took place in 1967; the age of consent was equalised at 16 in 2001; while same-sex marriage was legalised as late as 2014.

This leads us to consider why some campaigns fail or take such a long time to succeed. Of course, one person’s opinion about what is progress may be another’s idea of corruption or decline. And it’s always worth being aware of who could lose power in any challenge to tradition.

So, what changes can we expect over the next twenty years?

We can see echoes from our past in which direction we may be heading.

The Bay’s population is projected to rise from 139,000 to over 153,000. As part of that ongoing urbanisation, we will inevitably become far more diverse and multicultural.

Currently the average age in the Bay is 49; nine years more than that of the UK. Due to remarkable health and social advances in the past half-century and an inflow of retired incomers our average age will increase further.

As we saw with the coming of the railways, technology, this time in the form of automation and Artificial Intelligence, will progressively affect how we work and distribute wealth and opportunity.

But while the industrial revolution made Torquay the wealthiest town in the nation, it also created a fragmentation of society and a polarisation between social classes.

The danger is that, though many of us will see the benefits of the latest technological innovations, others may fall behind. We may then revisit the downside of change and again see divisions between: the rich and poor; locals and incomers; the young and old; the town centre and the suburbs; homeowners, renters and the homeless; and between the loved and the lonely.

But while accepting that change is constant, we don’t have to accept that we are powerless to influence what our future is. This time we have the knowledge and ability to tackle climate change, to design a more equal and cohesive society, and to really harvest the potential of new technology for us all.

Most of all we need to recognise that while change is inevitable, progress isn't. What matters now is what kind of Torbay do we wish to live in and how we make positive change happen.

The coming of the railways in 1848

The coming of the railways in 1848