Gallows Gate

There’s an old story that tells of how a sheep hanged a local thief.

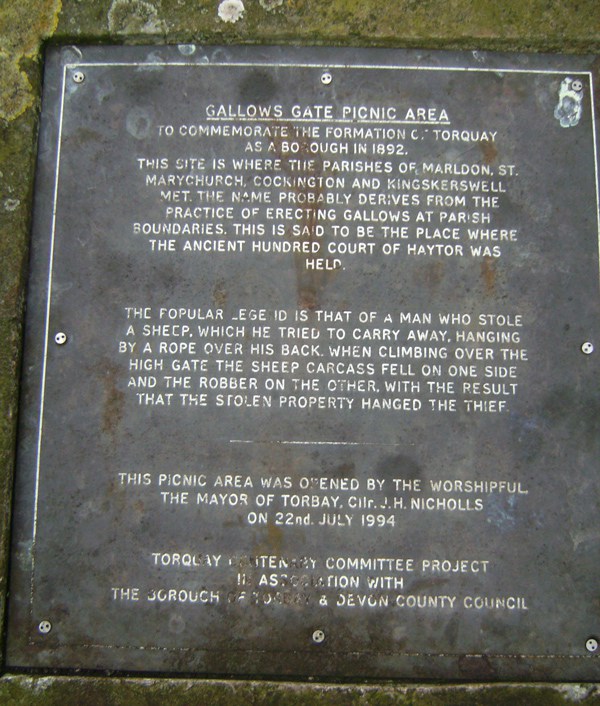

First of all the location. Gallows Gate is at the top of Hamelin Way on the A380. At around 495 feet above sea level, the site is on an ancient ridge way and where the four parishes of Cockington, Marldon, Kingskerswell and St Marychurch meet. You can read all about the supposed incident at the gate where there’s a plaque which recounts:

“The popular legend is that of a man who stole a sheep, which he tried to carry away. Hanging by a rope over his back when climbing over the high gate the sheep carcass fell on one side and the robber on the other with the result the stolen property hanged the thief.”

There’s even a gate to be seen. It is, however, a relatively recent addition, a stage-prop for the allegory, a gate to nowhere.

So, did it really happen and when did it supposedly take place?

It’s a nice story but has one major flaw. We’re not alone in telling the tale. There are around thirty places in England with a place called Gallows Gate, or a large boulder called the Hangman’s Stone. What we’re reading here is a legend, the aim being to hand on accounts of events alleged to have occurred. They are generally recounted for entertainment value, the objective being to explain, warn or educate.

The earliest British record of the ‘sheep hangs man’ legend is in Thomas Westcote’s ‘A View of Devonshire in 1630’, referring to Combe Martin in North Devon. Other sites are in Berkshire, Gloucestershire, Sussex and Yorkshire.

In Devon there are nine places with similar hanging legends, with five being on Dartmoor. The tales from the Moor are often associated with ‘hangingstones’ which acquired their names from the ‘hanging’ ceremony during a parish beating of the bounds.

The story also seems to change depending on what animal is locally most prevalent and worth stealing. For example, the first apparent telling comes from 1560 in Switzerland, though this was a pig rather than a sheep. In Leicestershire, it’s a deer.

In our part of the world, the legend reflects the importance of sheep farming and serves to warn against sheep stealing. The message was that even if the Law didn’t punish you, then God would.

A shortage of food was common, particularly during the winter, and one sheep could feed a family for a month. But sheep were easy prey, more compliant than cattle, a good size and often left in open fields. Also, once converted to mutton, pilfered ruminants are difficult to identify. Hence, theft appears to have been commonplace and the story may also telling us that a lot of thieves were getting away with their crime, despite the efforts of the authorities and the severe penalties.

We may be seeing evidence of social change. The growth of towns such as Torquay was introducing a new kind of criminal. Good country neighbours had long-established traditions of mutual support. They would never steal from one another as they knew that the loss of a single animal could lead to the death of an entire family. The story then suggests that the thief was an outsider and an idiot as a farm hand would know how to handle rope and not make such a simple mistake. Accordingly, this may be a yarn told by country people about thieving townies.

The location of the story, by Torquay’s place of execution, is significant. It was a place where justice was seen to be done. Death by rope, either by man or by God.

This is a very ancient place. The Haytor Hundred is recorded as being held at Kingsland (the King’s Land). This would have seen gatherings of men called to fight and hold open air courts, as well as providing a good lookout for sighting hostile ships in the Bay. The partition of Devon into Hundreds dates from King Alfred (871-901) and so this indicates that Gallows Gate served for well over a thousand years as a place of execution. A lot of folk lost their lives on that Torquay hilltop.

Many offences were introduced to protect the property of those wealthy classes that had emerged during the first half of the eighteenth century. It was intended that the law should act as a deterrent. This was also the reason why executions were public spectacles until the 1860s. Justice needed to be seen to be done and so criminals were left to rot at execution sites. An additional moral lesson about God’s justice wouldn’t do any harm.

In 1723 The Black Act created fifty capital offences for various acts of theft. This became known as the Bloody Code which, over time, imposed the death penalty for over two-hundred offences. These included: stealing from a rabbit warren; writing a threatening letter; pickpocketing goods worth a shilling; being an unmarried mother concealing a stillborn child; wrecking a fishpond; “being in the company of Gypsies for one month”; “strong evidence of malice in a child aged 7–14 years of age”; and “blacking the face or using a disguise whilst committing a crime”.

In 1741 came a specific law entitled, ‘An Act to render the Laws more effective for preventing the stealing and destroying of Sheep’. This was a time of rural hunger, high prices and escalating temptations for the starving. In response, the legislation explicitly identified the death penalty for the increasing incidence of rustling.

We don’t know the exact number of hangings for that offence. However, between 1825 and 1831 alone 9,316 death sentences were passed in Britain, 1,039 for sheep-stealing.

But not all the convicted were hanged. Whilst executions for murder, burglary and robbery were common, death sentences for minor offenders were often not carried out. Between 1770 and 1830, for example, an estimated 35,000 death sentences were handed down in England and Wales, of which 7,000 executions were actually carried out.

There were, by then, alternatives to the death penalty, such as imprisonment and transportation.

As the nineteenth century progressed the numbers of executions fell. In 1831 only 162 persons were sentenced to death for sheep-stealing in England and Wales, with a single execution being carried out. This was around the time that Torquay’s Gallows Gate seems to have been relocated from its prominent hilltop position. Tourists just didn’t want to see rotting corpses hanging on the skyline overlooking a modern town.

It was not until 1832 that sheep, cattle, and horse stealing, along with shoplifting, were removed from the list of felonies for which you could end up at the end of a rope.

It was also being realised that there were unintended consequences of the Bloody Code as draconian laws encouraged even greater crimes. Back in 1678 John Ray’s collection of English proverbs identified the problem: “As good be hang’d for an old sheep as a young lamb”. We still use the saying today.

Kevin Dixon is the author of ‘Torquay: A Social History’

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.