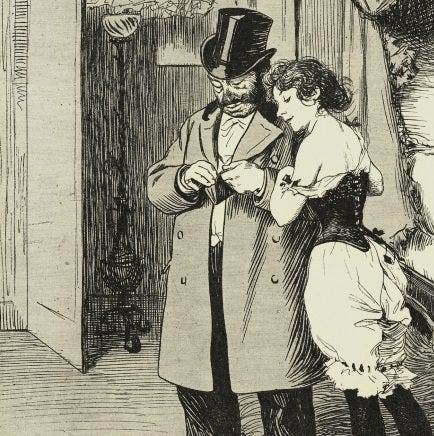

"Filthy picture postcards often led to a loose and unclean life"

In 1853, Torquay’s Chief Constable, Charles Kilby, complained of the “unbecoming manner that young women of the town wander around the thoroughfares without bonnets and shawls.”

This wasn’t just a snobbish comment on youthful fashion choices. It was code.

The subject was the ‘fallen women’ of Torquay, those that had ‘lost their innocence’ and fallen from the grace of God. Here was the biblical harlot. Indeed, the topic was so troubling that even identifying the practice was distasteful.

Charles was implicitly recognising that prostitutes dressed in a manner contrary to customary female attire. They often wore gowns made from colourful material that accentuated their body shape, and to promote their offer, they didn’t follow the practice of wearing modest bonnets and shawls in public.

Here were Torquay’s outcasts, venturing forth from the beer houses and tenements of Pimlico and Swan Street to shamelessly parade the streets in their tawdry clothing. In contrast, men’s sexual desires were seen as an inevitable result of their natures. Effectively, men were not to blame. It was always the doxy and the strumpet.

Torquay has always had its ‘ladies of the night.’ But we also need to recognise the town’s long-established gay subculture and the presence of male sex workers, an even less explored aspect of local working-class history.

While we have fragmentary evidence from Torquay, we do have a great deal of research from other locations, particularly the capital. And Victorian Torquay consciously replicated London, adopting its fashions, terminology, and even place names such as Pimlico and Belgravia.

From this research, and even though the estimated numbers of Victorian sex workers differ, it seems likely that there would, at times, have been several hundred Torquay prostitutes, a significant part of the working class of our town.

Though prostitution was common throughout the nation, Torquay also had its unique characteristics. It was described as the wealthiest town in England, and the affluent needed a large servile class, a majority of those in service being women and girls. In 1881 there was a population of 19,293 females but 13,665 males.

While some women entered prostitution by choice, attracted by its comparatively lucrative remuneration, many were forced or had no other option. For those not able to secure any employment, there were few alternatives.

Particularly vulnerable were those women who had been lured to Torquay with the promise of employment and accommodation.

Having left their home villages, they lost the protection of their families and could be seduced or forced into sexual liaisons by fellow workers or employers. And it is amongst poorly paid and bored, servile staff that we find the ‘dolly mop,’ the amateur, part-time sex worker.

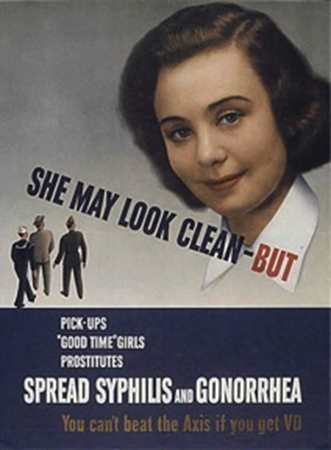

Above: Luftwaffe attacks weren’t the only danger to Allied servicemen in the Bay

It was in this setting that we saw a reservoir of women, men, and children available to satisfy the sexual requests of clients. A high demand was always there from holidaymakers, replaced every week or so, and with money to spend. In effect, both supply and demand were constantly being replenished.

From other towns and cities, we read of a robust sex-worker subculture that clearly distinguished prostitutes from other working-class women. Many prostitutes formed strong ties with one another, though this was still a world of violence, squalor, alcohol, opium dependency, exploitation, and intimidation, with fierce competition over territories.

Furthermore, the inevitable consequence of brief liaisons was left to the not-so-tender attentions of baby farmers; the most notorious local example being Charlotte Winsor, who in 1865 was convicted of the murder of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son at Lowe’s Bridge.

Other unwanted children were just abandoned. In 1849 a baby’s body was found in Warren Road, and in 1858 a baby was found floating off Anstey’s Cove.

The most common form of prostitution was streetwalking, and women could be found at night frequenting harbour pubs and Cary Green—the area in front of the Pavilion. This all seems to have been tolerated, though the authorities took note when things became too obvious.

Unaccompanied women, for example, were often assumed to be prostitutes.

In 1893 the landlord of the Marine Tavern pub near the Pavilion was accused of assaulting a policeman and for being drunk and disorderly. However, the defence argued that he was sober and that he had only taken offence when a passing policeman had accused his wife of being “a woman of loose character.”

Above: Torquay’s lost Marine Tavern

According to the landlord, he had been waiting at the Fish Quay for the arrival of the ferry. At one point he left his wife alone, and a policeman approached her.

That’s where reports began to differ. The police said the landlord went berserk and had to be restrained. The landlord said that he was badly beaten. Despite a number of witnesses saying that the landlord was sober and of good character, and familiar accusations that Torquay’s police had a tendency towards being heavy-handed, the court accepted the testimony of the police. The publican was jailed and lost his living.

Generally, however, the activities of Torquay’s poor were rarely acknowledged… unless they attracted the attention of the authorities or reached the courts. Only occasionally did a public example have to be made.

In 1899 the landlord of the Abbey Inn on Abbey Road was charged with allowing his pub to be used as “a habitual resort of women of ill fame.”

A detective Thomas had watched the inn between the hours of 8 and 11. “He saw women of loose character enter. They stayed for a considerable time—between 10 and 25 minutes. They entered and returned several times on the same evening, sometimes alone and sometimes in company with men… Entering the inn, he saw three loose women in one of the rooms.”

Women of good character were unlikely to visit an inn alone, and so evidence of impropriety included a notice instructing females not to remain in the house for more than a quarter of an hour.

On one occasion the detective heard the landlord shout, “Time, ladies!” indicating that women were not being escorted by a man.

The defendant protested on his arrest, “What can I do with so much rates and taxes to pay? They bring me my living.” Disregarding this defence, he was fined £5 with £1 costs, and the brewery took away his tenancy.

For well over a century, the message remained the same. There were dangerous women on the streets of Torquay.

In early 1914 a ‘Big Meeting of Men’ was held in Torquay Town Hall by the YMCA; the 800 young men present were warned that: “Hundreds of lads went under in the moral life every year either through ignorance or curiosity. Filthy picture postcards often led to a loose and unclean life. In Torquay there were thousands of girls and women decking themselves out in bright clothing and donning tawdry jewellery that they might walk the streets and try to attract so-called men and young men.”

Above: In 1914 a ‘Big Meeting of Men’ held in Torquay Town Hall warned of the dangers of consorting with women

Even as late as the Second World War, it was deemed necessary to issue warnings of the hazards lurking on the home front. When RAF trainees were billeted at the Grand Hotel in 1940, “an ancient aircraftman” warned them that, “There are lots of ladies down here from London who hand out bags of sweets.” It was only later that the trainees realised what their lecturer had been alerting them to.

It was the introduction of the welfare state that reduced the poverty that caused many to take up the oldest profession. Though even into the 1950s, women were still to be found loitering on the Strand, waiting to take their customers to the darker recesses of Rock Walk.

Of course, sex work continues in Torquay. Now, though, it is often to be found amongst women with alcohol and substance dependence or those trafficked into town. We accordingly applaud the work of the local organisations that are out there offering those vulnerable women support.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.