A recent national newspaper article claimed that Torbay “has become overrun with drunk gangs of nine-year-olds who mock cops to their faces and beat up adults.”

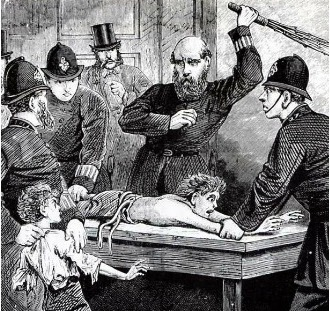

This isn’t the first time that the young have both generated and experienced fear and loathing in the Bay. But it was only from the beginning of the twentieth century that young miscreants were seen as being different to any other criminal. Indeed, they were treated just as harshly as their adult counterparts.

Torquay’s court records from 1850, for example, tell us that:

Stephen S, aged 13, was given “12 stripes” (flogged) for stealing a tin of biscuits, value one shilling.

Matthew R, aged 14, received three weeks hard labour for stealing strawberries from a garden.

Three boys, aged 12, 11 and 10, were found guilty of cutting the hair from horses’ tails in a stable in Temperance Street and selling it. The oldest two were each given “12 stripes and to be confined in a reformatory until the age of 16″. The youngest received 12 stripes.

However, during the early twentieth century attitudes began to change. Young offenders were given different trials through special youth courts.

Above: Nineteenth century youth justice

A rising crime rate following the First World War caused particular concern and was seen to be caused by boys lacking adult male role models. This was cited in 1925 when a juvenile crime spree shocked the sedate resort.

Over a period of twelve months, shops, huts, stores, and cars were broken into and tents ransacked “causing much damage”. Over £40 of property was stolen; a significant sum when the average male weekly wage was about £5.

There was public outrage. The police were baffled and came in for much criticism.

Eventually, in February 1926 there was a breakthrough when nine boys between the ages of 14 and 17 were arrested.

The surprise was that these were “local lads, well dressed and of good appearance”.

Torquay had always assumed that criminals either came from beyond the town’s boundaries to exploit our good will; or that local lawbreakers were from the lower, uneducated, and untamed classes.

The lads appeared at Torquay Police Court having been found in possession of “an astonishing conglomeration of articles”. The gang even had a hideout where all this booty was stored, described as old smugglers’ caves near Hope’s Nose.

Further alarming the authorities was the discovery that that the gang had embraced new and dangerous technology. In one cave there was a telephone and 800 yards of telephone wire, stolen from the Devon Territorials. The plan had been to connect the two caves via telephone.

This was only one indication of the sophistication of the “band of robbers”. Another member was “a clever mechanic” who had “taken impressions of keys and made duplicates to gain access to a shop in Ellacombe.”

Predictably, the cause was identified as being the lads liking for “reading trashy literature and witnessing highly sensational films”.

Mr Hutchings, who appeared in the boys’ defence, asked whether they had “learnt that kind of thing at the pictures. The sooner such pictures are stopped the better”. Although Mr Hutchings “did not attend the pictures, some of the posters he had seen were quite sensational enough to put ideas into young heads.”

The boys were all found guilty and bound over for 12 months. The three ring leaders were further ordered to pay 10 shillings towards the costs.

Above: Torquay’s backstreets, the haunt of feral youth. Park Lane. The Hole in the Wall to the right

Yet, the threat of juvenile delinquency continued. In 1931 the Torquay Directory told of a ‘gang’ that had “terrorised” Babbacombe.

The same issue reported, without irony, on another gangster called Al Capone who was similarly “terrorising” the citizens of Chicago.

The newspaper wasn’t that clear what the offences were, though they did relate an incident where, “One resident fell a victim of this malign gang, was subjected to an outrageous attack in the dead of night, while he was in bed, his house was ‘stoned’, and his front door badly damaged”.

Whatever else the hooligans had been up to, the paper declined to be specific and used the general term “evil activities”. In response, “The Police had already been called in and from time to time have captured some of the members”.

To prevent the situation from deteriorating further a plain clothes police officer was sent to scour the streets in search of the evildoers. The officer selected was the amusingly named PC Gammon who tracked the gang down to Victoria Park Road.

According to reports, “He saw the entire gang playing football in the roadway. As he went towards them, one of them suspected his identity and shouted to his comrades ‘Look out. Policeman!’ It was too late, however, the entire gang, seven in number, were caught red-handed. One of their number was inclined at first to be defiant and he exclaimed ‘Me! All right, we’ll see about that’.”

At Torquay Police Court the offenders pleaded guilty to playing football in the roadway. The young men, who were “employed as caddies and errand boys”, were fined heavily, at around a week’s wages each. The Magistrate warned them that they would not get off as lightly next time and promised them that, “We are not going to have Babbacombe turned into a hooligan’s preserve.”

Torquay's Police were delighted at their gang-busting operation, “From the Police point of view, it was undoubtedly the most successful round-up since the gang have been in existence.” Indeed, in comparison, it took over 10 years for the Chicago Police to convict Al Capone.

Since 1964, when Mods and Rockers started the tradition of seaside rioting, Bank Holidays had the potential for trouble. Yet, unlike Brighton, an easy scooter or motorbike ride from London, Torquay was generally too much of a trip for the new ‘folk devils’ of popular culture. However, Bristol and Plymouth were only hours by train.

In 1970 Richard Allen’s youthsploitation novel ‘Skinhead’ had been published, “a story straight from today’s headlines – portraying with horrifying vividness all the terror and brutality that has become the trademark of these vicious teenage malcontents.”

Now the skinheads had a script to work to.

Torquay had its first skinhead experience during the Easter weekend of 1970.

The Torquay Times wrote of the “the latest teenage cult of violence… an invasion… the crop haired youngsters dressed in their adopted style of jeans, heavy boots and sporting near-shaven heads, first caused trouble on inbound trains on Good Friday. Carriages were damaged… During the weekend there were occasional scuffles along the sea front as lines of chanting teenagers linked arms across the road and halted traffic.”

On Easter Sunday a car was rolled into the sea from North Quay, and fittings on boats were damaged.

The weekend violence became a regular event in tourist resorts throughout the country. By August, the skinheads found someone to fight with.

“During last Sunday’s rampage by Hells Angels and Skinheads, a crowd of 200 on Torquay seafront scuffled with police – and a Newton Abbot man trying to telephone an ambulance was dragged out and beaten.”

A taxi driver was on hand to comment, “If Torquay gets a reputation for this sort of thing, it will kill the area as a holiday resort. Many of the youngsters act like wild animals. They need a real lesson – not a couple of quid fine.”

And so it goes on. The nation is seen to be always under threat from youth gone wild, enabled by soft-hearted liberals, judicial softness, and undeserved working-class luxury.

The solution is often the same. A 'clamp down' on youth crime and a 'zero tolerance' of 'anti-social behaviour' which will return us to the peaceful Bay of just a generation ago. But, underneath are much broader concerns about social change, morality, the role of the media, and around what our national culture was and now is.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.